By Oluwayeni Odifa

There is a quiet violence in being called African and nothing else.

In the name of unity, many have begun to strip themselves clean. Of dialects. Of names. Of skin-toned particularities. In global forums, on social feeds, and even in African conferences, a strange amnesia sets in. Everyone wants to be African, but few seem willing to be Wolof, Xhosa, or Yoruba first.

Pan-Africanism, once a revolutionary force of self-determination and cultural pride, now risks becoming a hollow aesthetic. What started as resistance against colonial fragmentation now teeters on a new kind of erasure. One that wipes away what makes us distinct, not just from the West but from each other.

We are not the same, and we were never meant to be. That is not a weakness.

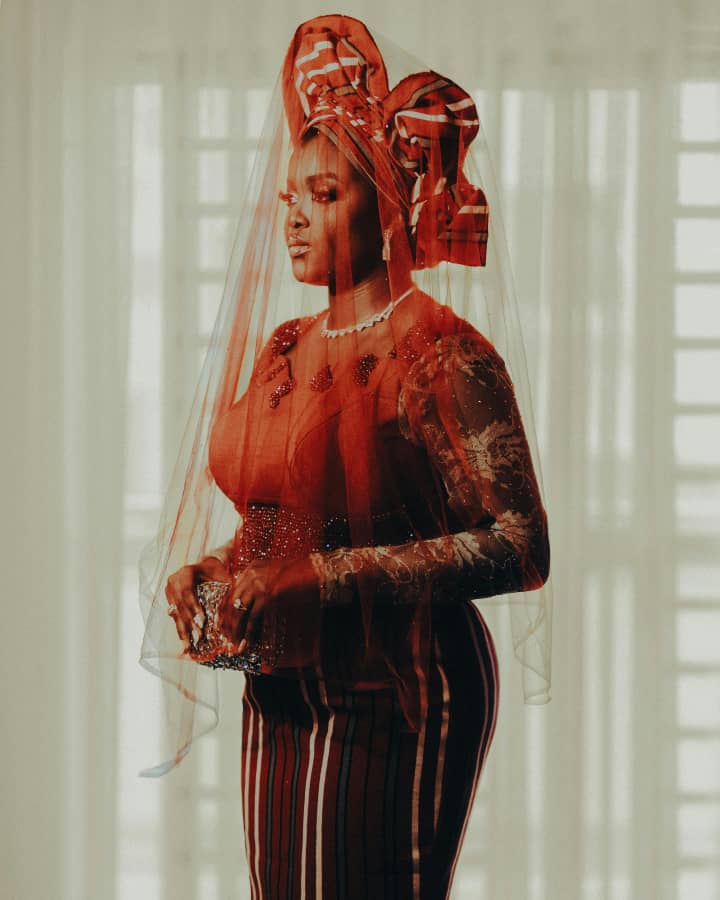

To be Yoruba is to inherit a rhythm of thought shaped by culture and lineage, grounded in a system of ancient practices. It is to name a child with intention, to find wisdom in proverbs, and to build with diligence for self and kin. These things cannot be collapsed into a flattened Black identity. The uniqueness of every group is theirs to know and keep.

But in today’s curated Pan-Africanism, you are rewarded for proximity to Black American culture, or Caribbean speech, or the general idea of Africa as one large, vague ancestral home. The marketable kind. Dashikis with no tribe. TikTok dances with no language. Afrobeat without dialect. A unifying flag with no roots.

It is not that unity is the problem. It is the kind of unity that refuses to pass through the door of specificity.

When we do not protect our local identities, we create a version of Africa that is easily digested by global systems but rarely understood by those who live within its borders. A version where Accra, Nairobi, and Lagos become content hubs rather than cultural cities. Where young Africans feel more pride in being “from Africa” than from the very towns that raised them.

A Lagos teen apologizes for their Yoruba accent. A Congolese designer swaps out Kuba motifs for “tribal” clipart. These are not isolated choices. They are quiet acts of survival in a world that rewards African generality over depth.

The flattening of African identity is not accidental. It is accelerated by social media trends, global market aesthetics, and even some NGO messaging that rewards simplification over specificity.

Calls for Swahili to become Africa’s single language may sound like unity, but they often echo the same logic used by those who once tried to colonise us. Language, like land, carries memory. Imposing one on all dishonors the others.

For many in the diaspora, a singular “Africa” offers emotional refuge from histories of loss and fracture. But even healing must move from symbol to substance.

You cannot build enduring bridges without firm land on both sides. To connect meaningfully, we must stand in who we are. Language. Land. Lineage. From there, we reach outward. Otherwise, we mistake mimicry for solidarity and branding for belonging.

Somewhere, a child speaks English because her parents believe her mother tongue will hold her back. Somewhere else, a designer pastes an ethnic symbol she cannot read onto a shirt for a global drop. We are losing things. Sacred, tangible things.

Pan-Africanism cannot work if it demands we enter the room with our differences zipped tight. It must instead invite us to arrive fully. With our Ogbomosho. Our Banjul. Our Kigali. Our Jo’burg. Not as tokens of diversity, but as building blocks of the real.

Because Africa will not be saved by sameness. And we were never meant to be identical.

Even the architects of Pan-Africanism, from Nkrumah to Sankara, understood that true solidarity required respect for local roots, not their removal.

A unified identity can be powerful in global advocacy, but not if it costs us cultural integrity. We do not have to choose between being many and being one.

The future of Africanism should mean building factories before hashtags. It should mean local manufacturing, inter-African trade, and continental priority in commerce. Not the erasure of languages or the adoption of one “African” aesthetic. Our true power is in cultural self-respect, not cultural uniformity.

–

Start where you are. Speak your language. Know your lineage. In your grandparents’ village. From there, build outward. Before you post, speak, or represent “Africa,” ask yourself this: Whose Africa are you carrying? Start with your roots.